Analogue Duo: The Kotaku Review

You know Analogue: The company that makes those premium-priced retro consoles that sell out in three minutes, at which point Analogue tweets “Sold out.” as if you needed reminding that its damn website crashed while you were struggling to complete your purchase. But while Analogue can be exasperating, its products, which include high-end recreations of the Nintendo Entertainment System, Sega Genesis, Super Nintendo, and all the Game Boys, more or less deliver on their promises of exceptionally accurate reproduction of beloved video games from decades past.

Today the company’s launching another retro console recreation, the Analogue Duo. And this time, it’s something of a deeper cut.

Just…god, there’s so much random info you gotta know to understand this thing’s deal. So before we get into it, here’s a tl;dr: Analogue Duo is a very solid PC Engine / TurboGrafx-16 replacement that looks pretty good on modern displays and controls pretty well, too. It’s also not for everyone. It may not even be for me.

To get at why, we need to dive into those nitty-gritty details. For starters…

What’s a PC Engine?

If the name “PC Engine” doesn’t ring a bell, that might be because it flopped here, hard. Co-creators NEC and Hudson (the Bomberman people!) saw good success in Japan, but NEC botched just about everything in its attempt to market the sorta-kinda 16-bit system in America as 1989’s TurboGrafx-16, a name which now reeks of death and failure. Many of the best PCE games remained in Japan, and most of the ones NEC commissioned from western creators are best left unmentioned. Sega of America’s Genesis ate it for lunch (CW: vore), leaving the TurboGrafx on life support by 1992.

Not so in Japan. Debuting all the way back in 1987, the PC Engine was a shot across the bow of Nintendo’s dominant Famicom (NES), offering far more arcade-like graphics than the 8-bit king ever could. Barely a year later, the CD-ROM² add-on made NEC’s little square wonder-console the first machine to play games off optical discs, allowing for the creation of far more sophisticated software with lush CD audio, extended animated sequences, and some 1,000 times the storage of the system’s original HuCard format. In 1988!

HuCards are beautiful

HuCards (TurboChips over here) were the PC Engine’s equivalent of cartridges, credit card-sized slabs of plastic that slid into the front of the system with a satisfying click. Often emblazoned with colorful artwork, these diminutive little things are likely the most beautiful physical format ever used to distribute video games. (A few downsides include limited ROM capacities and zero user-serviceable parts.) Over time CDs became the PCE’s dominant format, but consider this: Only HuCards can fit in your wallet. Checkmate, you optical bastards.

NEC had a real passion—some might say a psychological disorder—for releasing new PC Engine hardware. It’s a bit much to cover here, so just know two important facts. First, 1991’s Super CD-ROM² upgrade gave the disc games four times more RAM to play with, which let the new “Super CD” games be more sophisticated, especially graphically. Many of the system’s coolest games, such as Ys IV, Star Parodier, Tengai Makyō II, Dracula X, and Gradius II, are on Super CD.

Read More: Alien Crush Made Pinball Weird, Squishy, Gross

Second, 1991’s PC Engine Duo (TurboDuo in the U.S.) was a handy, all-in-one console that could play both HuCard and Super CD games. Duo is the system most people want to own today, because this thing plays everything but the five games released for 1990’s ill-fated SuperGrafx (no one cares) and games that require the later, 1994 Arcade Card RAM upgrade (just pop in the Arcade Card accessory and you’re set).

So the PC Engine Duo is the machine today’s Analogue Duo takes its inspiration from. Except, Analogue Duo can play the SuperGrafx games and the Arcade Card games out of the box, too. Cool!

…And why should I care?

If you’ve ever retrogamed, you’ve probably enjoyed time with a Sega Genesis or Super Nintendo, yeah? Incredibly good consoles, some might even say the best of all time. These 16-bitters, which had their heyday from 1989 to 1995 or so, achieved a very pleasing balance of gameplay, simplicity, and sophistication, and could look and sound pretty great too. What’s the word for “kino” but like, for video games? Because that. These were video games. Ahhh, yes. The good stuff. (I am pantomiming chef’s kisses.)

Well, there’s another whole system full of video games like this that many of us haven’t dipped into at all, a treasure trove of fresh adventures and maddening challenges. I’m talking about the PC Engine, by the way.

Just like the Genesis and SNES libraries have their own distinct flavors and vibes, strengths and weaknesses, so does NEC’s ambiguously 16-bit wonder. The PCE library is particularly strong in arcade-style shoot ‘em ups, RPGs, arcade ports, platformers, and action games in general. Its games tend to be colorful and fast-moving, and its humble but pleasing sound chip can pump out some really catchy melodies (and occasionally amazing tracks like this).

Read More: The Unique Artist Behind Bomberman’s Catchy Beats

Strangely, it also has major Famicom vibes. The PCE’s 8-bit main processor has basically the same architecture as the NES, and it’s only faster clocks and additional graphics chips that make its games so much fancier. A lot of its games, particularly early HuCards, have a sort of loosey-goosey simplistic physics thing going on that feels very NES-like. PCE sorta feels like an evolutionary midway point between Famicom games and 16-bit SNES and Genesis titles, very much its own thing, but sharing aspects with the others.

So is it 8-bit? Or 16-bit?

Oh, yes. Absolutely.

Sadly, PC Engine can’t do convincing parallax scrolling to save its life. But then, neither can I. (So don’t ask.)

The most important acronym in retrogaming

It’s FPGA: Field Programmable Gate Array. Stop looking at me like I’m a nerd. I’m aware.

You know how regular microchips are burned permanently onto silicon? They’re ASICs, which stands for “application-specific integrated circuit.” The CPU in your cell phone is good at what it does, but it’s never gonna be anything other than what Qualcomm or Apple designed it to be because its silicon is fixed. Immutable. Set in its ways. Basically, ASICs are the racist grandpas of integrated circuits.

Wait…I am being told that is not a useful analogy. Apologies. Racist grandmas, then.

FPGAs, unlike grandmas, are infinitely reconfigurable. An FPGA is like a blank-slate microchip whose circuits you can lay out and configure through a “hardware description language”—code that defines the hardware, basically. So say you have an FPGA chip to program; if the FPGA were big / performant enough and you really knew your stuff, you could write code in hardware description language and upload it to the FPGA to make it perfectly replicate the functionality of another device. Say, the CPU of the Game Boy. And then you could upload more HDL to reconfigure the FPGA into another device entirely. Maybe…the Sega Genesis’ sound chip?

You see where this is going. While FPGAs are still expensive, they’ve been getting affordable enough to put to use simulating old games machines. And it turns out this is a very good way to go about recreating old computers and consoles, as FPGAs are great at simulating many discrete components at once, all operating in parallel just like they did in, say, a real SNES. In contrast, traditional CPUs execute instructions in a mostly linear fashion, making it difficult to orchestrate all the moving parts of an emulated game console in a way that results in a flawlessly authentic experience.

Read More: Is MiSTer The Ultimate Retro Gaming Device? Yes, Actually

The biggest drawback of traditional software-based console emulators running on CPUs is probably input lag. You press a button, and there’s a delay, and finally you see your action take place on-screen. (The most advanced emulators have pretty cool ways to reduce this delay, but it’s still always a concern.) Some of the main sources of input lag are modern display devices, your choice of game controller, poorly programmed games, and software-based emulators.

A vintage game console properly simulated on an FPGA can respond to input just as quickly as the original hardware did. That’s a beautiful thing, and a key reason many see FPGA-based devices, like the open-source MiSTer FPGA project and Analogue’s proprietary line of FPGA-based console recreations, as not just the present, but the future of accurate, cut-no-corners retrogaming.

CRTs: Slightly radioactive implosion bombs

Until the mid-2000s, most people played video games on heavy glass vacuum tubes that imbued the soft, somewhat indistinct pixels with a pleasing glow, horizontal scanlines, varying levels of barrel distortion, and many other artifacts besides. These standard-definition (SD) analog televisions and monitors, called CRTs (critical race theories), generally enjoyed lightning-fast response times, great motion clarity, vivid colors, and deep, contrast-y blacks. Video games looked and felt a certain way thanks to the particulars of the display tech, granting their low-res “240p” graphics surprising amounts of soul.

The fixed-pixel LCDs that followed usually made vintage SD games look blocky, uneven, and smeared, topped off with delayed input response: No bueno. Since then, software innovations like scanline filters and CRT-simulating GPU shaders, combined with new technologies like high dynamic range (HDR), black frame insertion (BFI), variable refresh rate (VRR), and purpose-made upscaling devices, have started addressing the considerable challenge of authentically rendering SD analog signals on digital-first, HD, fixed-pixel displays. Bolstered thus, today’s high-end OLEDs can finally start to reach or even surpass CRT-like levels of brightness, saturation, contrast, and motion clarity.

In other words, they’re gittin’ gud at lookin’ old.

That brings us to the Duo. At launch, Analogue Duo outputs only digital HDMI at 1080p resolution. Analogue promises that in 2024, support for its Analogue DAC accessory, an additional $80 purchase, will allow the Duo to work with traditional CRT televisions, a combination that will instantly grant its games a near-flawlessly authentic look and feel on SD analog displays. But until then, the Duo is strictly a digital, 1080p device, which leaves its “Original Display Modes” feature—Analogue frowns when you call them “filters”—as the main tool you’ll have to make PCE games look truer to their ‘80s and ‘90s roots.

The first Original Display Mode just spits out the raw pixels with appropriate scaling to the 1080p display: the basic, pixelated emulator look some people prefer. Two other ODMs simulate the ancient, early ‘90s LCDs of the portable PC Engine GT (TurboExpress in U.S.) and the very rare, expensive clamshell form-factor PC Engine LT. Neat little bonuses, but you’re probably not going to want to relive the days of TurboExpress’s ghosting, sub-native res screen garbling up text for very long. (Having never used either device, I can’t comment on their accuracy.)

The most interesting, attractive ODM is “Trinitron,” which seeks to reproduce the appearance of Sony’s famous CRT technology within the limits of Duo’s 1080p resolution, complete with faux scanlines (choose either Light or Heavy, then Soft or Sharp edges) and two possible renderings of aperture grille artifacts (“Medium” or “Fine”). You can also just nix the AG simulation if you want a simple plain-Jane scanline effect.

Two finer points

In the raw pixel and Trinitron modes you can also show or hide the overscan areas—hiding them gives you a bigger screen, but may cut off info in certain games—and choose between two color palettes, RGB or simulated composite. The latter is a relatively recent innovation, as fans discovered that the raw RGB colors put out by the PCE’s graphics chip actually varied from those generated by its native RF/composite output back in the day. It turned out some games have color gradations that are nearly hidden in the very hot, saturated RGB palette. As on MiSTer, I’ve used Duo’s drabber composite palette almost exclusively, because the RGB colors border on garish.

Trinitron mode does a decent job of simulating the basic look of a ‘90s Sony CRT and is my preferred way to play Analogue Duo. It is on par with some of the better CRT simulations seen in today’s commercial retro-themed game releases.

Duo’s undoubtedly pleasant CRT sim likely won’t blow you away if you’re familiar with today’s cutting-edge CRT shaders. It’s good for what it is, don’t get me wrong, but is too neat and clean, and also dim, to actually be mistaken for a real vintage set. CRTs are messy, analog devices, all soft and glowing, geometry at least slightly warped even when well maintained, everything contracting and expanding as scenes change, and bright objects leaving phosphor trails as they traverse inky blacks. All of this wonderful character, which makes CRTs so distinctive, is outside the scope of Duo’s otherwise respectable Trinitron simulation.

I’ve created some comparison sliders, captured over HDMI, to let you see how the various Original Display Modes and their sub-settings look. After clicking the links below, choose an image on the left, an image on the right, and then drag the slider to transition between them. (Thanks to imgsli.com for making these possible—very good website.)

If I could improve just one aspect of the Triniton ODM, I’d make it brighter. Adding faux scanline and aperture grille artifacts to a game screen is necessarily going to darken everything. Think about it: You’re laying down darker lines over many of the pixels, of course it’s going to lose brightness. But even with dark scanlines, a healthy CRT still puts out plenty of light. The same can’t be said for a typical fixed-pixel, non-HDR display of the sort Analogue Duo is designed for.

To achieve the best balance of analog character and brightness, my preferred settings were Trinitron / Fine / Soft / Hide Overscan. For reference, I played Duo on a BenQ XL2420Z TN LCD, an HP X27q IPS LCD, and an LG 48CXPUB OLED, all with brightness and contrast adjusted for maximum light output. The OLED, of course, looked the most vivid.

Duo does what it can to achieve a CRT look, but it fights an uphill battle against the limitations of the relatively humble, non-HDR, 1080p displays it’s designed for. Analogue’s upcoming FPGA Nintendo 64 console, Analogue 3D, will be a 4K-native device, and the company tells me its ODMs will graduate to a greater level of realism on that machine by harnessing advanced features like HDR, 120Hz, VRR, maybe BFI, etc.. Advanced PC RetroArch shaders and even MiSTer FPGA are already getting great results closing the fixed-pixel display brightness gap with HDR, so that in particular will be a welcome step toward a more convincing CRT simulation in Analogue’s products.

Of course, Duo is supposed to gain Analogue DAC support at some point next year. That will let it output 240p composite, s-video, component, and analog RGB signals to real CRTs. If you’re like me and greatly prefer to keep it analog for sixth-gen and prior consoles, then that $80 accessory may well be a must. But given Analogue’s delay-ridden track record, you might want to wait until Duo’s DAC support actually ships before committing to a purchase.

Everything’s under control

Like Famicom, PC Engine used simple, two-button controllers. They’re a joy to play on. In a wonderful touch, each button had an associated “turbo switch,” which could enable two different rates of rapid fire.

If you have old PCE pads, you can use them with Analogue Duo. Just like an original Duo, the new console only offers a single controller port (Japanese pinout, btw), so if you want to use up to five real controllers for games like Bomberman, you need a vintage multitap. That’s just a quirk of the PCE. Of course, the later three- and six-button pads are supported too, as is more esoteric hardware like this pachinko controller and Micomsoft’s analog XE-1 AP running through a converter. Attention to detail!

If you don’t have NEC pads, Duo also supports a wide variety of modern 2.4GHz and Bluetooth controllers. The most obvious to use is 8BitDo’s TG16 2.4G Wireless Gamepad, which Analogue supplied with Duo review units. This has been out for a few years already, so you may already have one. I’m pretty critical of 8BitDo controllers—the d-pads are often lacking somehow—but found its PCE clone compared nicely to original controllers in both comfort and d-pad accuracy, albeit with a less premium feel owing to near-zero heft. Its Home button is also host to several very useful Analogue OS shortcuts for opening the menu, saving states, switching ODMs, and taking screenshots. OG controllers get their own shortcuts, but seem to lack the ability to switch ODMs on the fly.

Missin’ switchin’

Instead of adjustable turbo switches, 8BitDo’s pads have two extra buttons that just always rapid fire. I would’ve preferred they keep NEC’s two-buttons-plus-switches design, which gave quick control over firing rate and didn’t lead to awkward diagonal thumb placements trying to straddle a normal and a rapid-fire button. You can still change the 8BitDo’s firing rate, but only via a secret, clumsy key combination.

The community has measured the 8BitDo TG16 2.4G to have about 7.5ms of latency (close to half a frame) when used wirelessly, which is pretty decent, and 1ms when plugged in. Which leads us to input lag. It’s pretty good! I mean, it’s pretty low. Everything felt good to play and responded quickly enough to avoid causing undue irritation.

But subjectively, I could notice the difference from my usual CRT setup. Analogue claims Duo has zero lag, and given the nature of FPGA consoles, I believe it. Instead, any perceived lag likely came from the HDMI displays and the wireless controllers. All three screens I tested added some level of delay, with the LG OLED feeling snappiest. Switching from 8BitDo wireless to a wired original controller helped reduce perceived delay further, though it was still arguably noticeable.

That’s not on Analogue though, it’s just the state of current technology. CRTs are still the gold standard for near-instant input response, and if the promised DAC support lands next year, Analogue Duo will hopefully get to feel snappy af on classic displays, too.

Building a better Duo?

While limits on time and available PC Engine software mean my testing was anything but comprehensive—my test suite included around 17 HuCards, 15 CDs, and one Turbo EverDrive PRO that I borrowed from a friend—as far as I can tell the Analogue Duo plays games exactly the same as a real PC Engine Duo. The games feel the same, play the same, sound the same, and (outside of the just-discussed HDMI display limitations) look the same as they do on real NEC hardware. Analogue did its usual bang-up job on the accuracy front.

It’s quite likely people will find issues here and there when the system gets into more hands, but Analogue is pretty good about addressing those through firmware updates.

Analogue Duo has, or will have in some cases, several advantages over original hardware. As mentioned, it can run SuperGrafx and Arcade Card software, which an unassisted PC Engine Duo could not. It’s also region-free; original hardware requires rare adapters to play U.S. HuCards on a Japanese system, and vice-versa. Of course, HDMI output is a big advantage these days, as is the support for an array of USB and wireless controllers. The headphone jack can boost its gain for high-impedance cans, which is thoughtful. Finally, it has two USB ports in back for wired controller use or for charging, and SD card support which allows for firmware updates, saving screenshots, storing game saves, and (at some point) saving states.

Unfortunately, save states and sleep/wake functionality didn’t make it in for launch. Analogue says to expect those in an update in Q1 2024, though save states will only be for HuCards, and it’s unclear if CD support will follow. Save states are a huge boon for old games, letting you pause your session at any point or cheat a bit to get past the tough parts. To be fair, MiSTer’s FPGA PC Engine core doesn’t support them either, so Analogue Duo will have a leg up there once those land.

“Just a moment…”

Besides analog video output, about the only OG hardware omission that comes to mind is Analogue Duo’s lack of facility to erase saved games on-console, which is traditionally handled in the CD-ROM² BIOS’ boot screen. This is very minor. Instead you would walk the SD card to a PC to delete stuff, but you wouldn’t really need to as storage isn’t at a premium anymore. The bigger issue: You won’t get to see the Duo’s classic boot screen.

While $250 isn’t pocket change, you could argue that Duo’s price is another advantage. Real PC Engine Duos start at around $180 for an untested “junk” unit, and it only goes up from there. The U.S. TurboDuo is considerably scarcer, so they start closer to $300 for a bare unit with cables and a pad. OG Duos are also notorious for rupturing their now-ancient capacitors, a problem which owners are strongly advised to head off at the pass with a preemptive recap. That’s at least another $80-$100 in electronic handywoman fees right there.

The only major functionality issue I have to report is that much like Analogue Pocket before it, Duo is…picky…about reading original cartridge media. I had zero trouble with a single CD, but several HuCards that work perfectly well on my original Duo were either shy about booting on Analogue Duo or wouldn’t boot at all. As with Pocket, Analogue’s main advice is to clean the problematic media thoroughly.

This eventually helped with three of the four holdouts, but one game resisted all attempts to boot on two different Analogue Duos. The system recognized it as Shinobi, but continuing only led to a black screen. If this reluctance to boot known-good HuCard media proves more widespread than it’s been here in my small sample size, it could prove a real drawback of the machine.

I f*cking broke it

When the Analogue Duo review unit arrived one of the first things I did was stick in the borrowed EverDrive, only to find it wouldn’t boot. I tried reseating it several times, but nope. Still very unfamiliar with the system and a tad desperate, I tried a flipped insertion, which required a little force. Didn’t fix it. What it did do, as we’d conclude after three days of troubleshooting HuCards, was all but ruin the system’s ability to read the things—this is me putting on my clown makeup. Thankfully, Analogue’s PR was super understanding and sent not one, but two more evaluation units. They must have thought I was going to destroy another.

The price of entry

Analogue Duo is a very capable PC Engine. So, have it! Go enjoy some games. Oh, err…You do own some PCE games, right?

You kind of need to, because original physical media is Analogue Duo’s preferred software delivery method. It wants you to click a vintage HuCard into that expectant slot, slip a 33-year-old CD into its pleasingly whirly drive. If you don’t have any lying around, then Duo won’t prove very much fun. You’ll get tired of reading the menus in five minutes, tops.

Retro prices are jacked

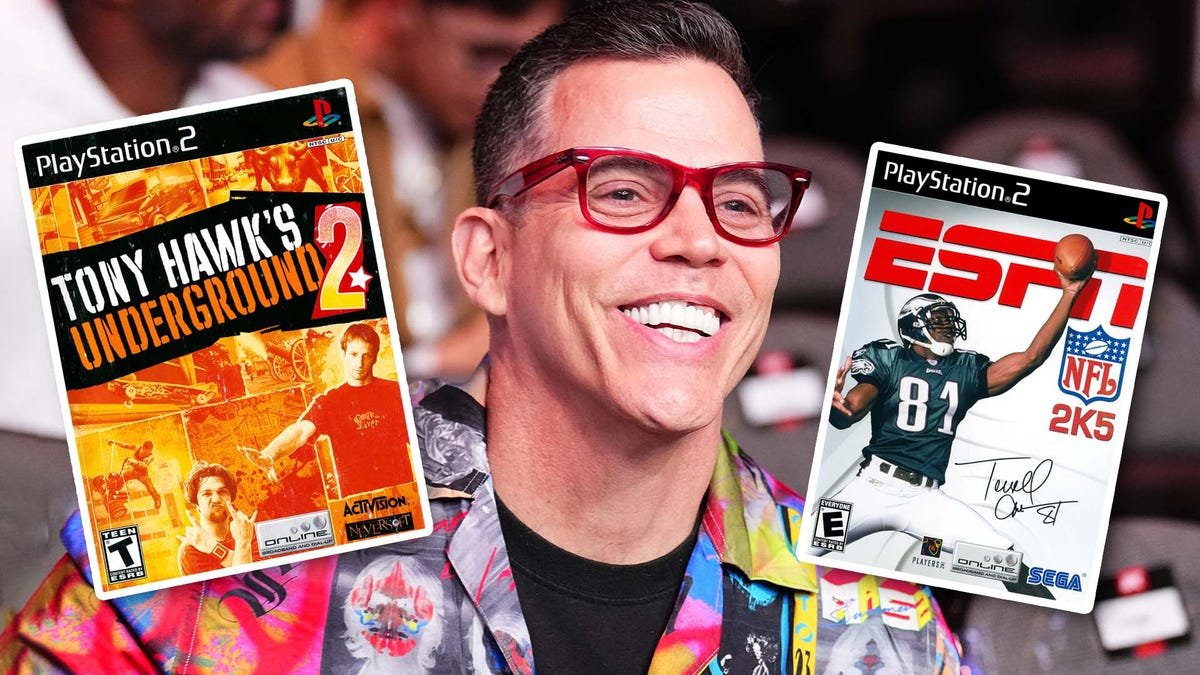

Have you seen how much old games cost these days? It’s absurd. Remember that photo above showing a TurboDuo and two Analogue Duos, surrounded by 14 PC Engine / TurboGrafx-16 games? According to auction-tracking site Pricecharting.com, that’s over $1,300 in software right there. If you didn’t buy them 20-25 years ago like this particular Xer did, are you really going to start investing four-plus digits into a PC Engine library today? That’d be kinda crazy, if you ask me.

You could get an EverDrive. EverDrives, made by a guy in Ukraine called Krikzz, are the most popular brand of flash cartridge for many classic systems, letting you load games from ROM files stored on a microSD card. They’re standard equipment for many retrogamers, and the Analogue Duo officially supports the Turbo EverDrive v2 ($89, only loads HuCards) and the Turbo EverDrive PRO ($220, adds CD game support). Still not cheap, but the idea is typically you can buy an EverDrive or similar device once and be set instead of racking up those four or five digits on second-hand game auctions.

A kind local friend let me borrow their Turbo EverDrive PRO (Model 22, Rev A mfr. 14 Dec 2022) for testing purposes. You need to remove its external metal shield to get it to fit into the Analogue Duo’s narrower HuCard slot, but it does boot up fine on the second unit I received, and Analogue says that if your particular Turbo EverDrive does not, that’s probably due to compatibility issues that Krikzz needs to, and intends to, fix.

Unfortunately, Turbo EverDrives may not be the panacea you seek. It turns out that because of peculiarities of the PC Engine, consoles that have a built-in CD-ROM drive cannot load CD games from the EverDrive. Hence, on a PC Engine Duo or Analogue Duo, Turbo EverDrives are only good for loading HuCard games, leaving over half the system’s library—some might say the more impressive half—inaccessible. Oof. I also found that opening the EverDrive’s in-game menu—very easy to do accidentally—would always crash the current game, so be sure to disable it. Maybe that is something else Krikzz will work on.

I noticed Duo doesn’t track your playtime of games loaded via EverDrive, in case that bothers you.

Btw CD-Rs work (lol)

While digging up my PC Engine games I happened upon a single CD-R containing the English fan translation of Ys IV. Analogue Duo played it just fine. So, that’s one possible solution to the Turbo EverDrive disc dilemma. On the other hand, can you really see yourself burning dozens of ISOs to discs in 2024? That’s a little too retro for me…

What about official unofficial ROM-loading support, which every Analogue FPGA console to date has, through some form of mysterious magic, received? “Analogue Duo was designed explicitly for original, legacy media within the NEC ecosystem,” Analogue told me. In other words, stop askin’ us about ROMs, kid.

Read More: There It Is: Analogue Pocket Just Got Its Long-Awaited Jailbreak

Odds are quite good that Analogue Duo will receive an unofficial “jailbreak” update at some point that enables loading of ROMs from the SD card, just as all Analogue’s prior systems have. But you may not want to purchase Duo immediately, if that’s important to you. (Good news on the waiting front. Says Analogue, “Duo is not a Limited Edition product. It will continue to be produced to meet ongoing demand.”)

I also have some level of concern that even after the theoretical jailbreak, Duo may still be subject to the “can only load HuCards” issue. But there’s no way of knowing, so all we can do is wait to see how the situation develops.

Definitely for somebody

By now you should have some idea about whether or not you want an Analogue Duo on your shelf. It’s undoubtedly an impressive recreation of one of the best video game systems of the 20th century, one that’s been a personal favorite of mine in recent years. I’m glad it exists—bring on the PCE love.

However, Analogue Duo doesn’t really suit my needs. I mostly play on CRTs—which Duo doesn’t support yet—and am looking to divest myself of my old physical game collection, not keep it around, or make it even larger. I am also well served by my MiSTer FPGA, which plays PC Engine games and everything else off of a tiny microSD card with very impressive accuracy. MiSTer is tied with my desktop PC as the single most capable and important games machine I have.

I think for most people the PC Engine is quite a narrow slice of the retrogaming pie to allocate a dedicated device to, and one that can only run rare old media. A MiSTer setup costs about twice as much, but simulates dozens upon dozens of classic consoles and PCs with an accuracy that easily rivals that of Analogue’s machines. Or a much less expensive RGB Pi uses software-based emulation to give a pretty good experience that’ll easily satisfy folks less inclined to be obsessive about all the little details. I’d go with either of those before a single-system console like Duo.

But Analogue knows Duo isn’t for “most people.” If you’re legit looking to start a PC Engine collection, if you’re a PC Engine freak who covets their carefully assembled hoard of vintage discs and HuCards, or if you just own and enjoy Analogue’s prior NES, Genesis, or SNES clones, then Analogue Duo, as it currently exists, may well be a good fit for your needs.

So, lots to ponder. I’ll leave the last word to Christopher Taber, Analogue’s founder and CEO, a passionate guy who is most assuredly a PC Engine superfreak (complimentary).

“We spent years developing Analogue Duo, to be the end all, be all,” he told me. “It’s pretty fucking insane. Who the fuck would ever do this on this level without a love for lost pieces of a beautiful medium, discarded. I can assure you we didn’t make it for the money.”