Brett Van Gaasbeek’s Students Talk about Preserving Self-Government

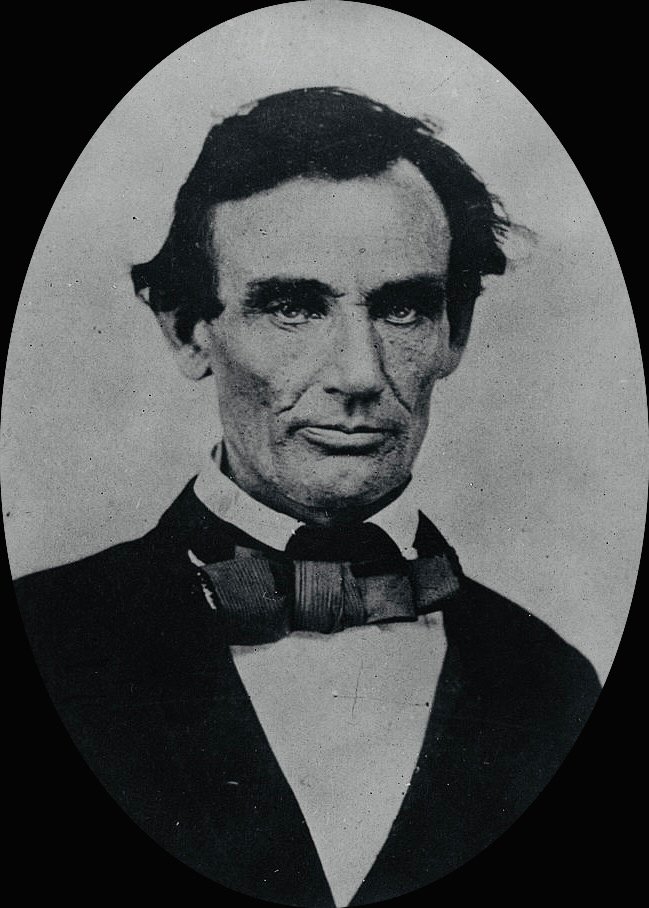

Recently I emailed a question to teacher friends who are graduates of the Master of Arts in American History and Government (MAHG) program. “How do you teach students about the challenge of preserving self-government?” Brett Van Gaasbeek replied that he relied on Abraham Lincoln’s analysis of the challenge.

Van Gaasbeek teaches a “College Credit Plus” US History course to sophomores enrolled simultaneously at Northwest High School in Cincinnati and at Sinclair College, where they earn college credits for course. The fast-paced survey covers American history from Columbus to the present day. Early in the fall, Van Gaasbeek’s students had read Lincoln’s 1838 speech to the Springfield Lyceum on “The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions.” They “nailed the section on mob rule,” he said. Since that time, they had recalled the speech during discussions of “the Civil War, the formation of unions leading to violent strikes, the rise of the KKK in the 1920s, and unrest associated with the Great Depression.”

Impressed, I asked Van Gaasbeek to tell me more. He replied, “Why don’t you chat with the students themselves?”

We arranged a Zoom meeting, where I met Van Gaasbeek’s honors-level students, a diverse mix of African-, European-, and Asian-Americans. I asked them, “What have you learned about the challenge of preserving self-government? What problems have Americans repeatedly faced in our history?”

A tall young woman with intricate, shoulder-length braids stepped forward to the video monitor. “I’m Madisyn,” she said. “One thing that seems to come up a lot in our history is corrupt government leaders, people who go into politics just for power, not because they want to make needed changes.”

Jyair introduced himself, then spoke of unequal economic outcomes. Not all Americans are financially successful. “Each new president tries to find ways to help people earn enough to avoid going bankrupt.” But none have yet solved the problem.

Amora, thin and blonde, pointed to the many disputes over taxation. Government needs money to operate, but citizens object to taxes, whether these are the tariffs of the 19th century or the income and capital gain taxes of today. Meanwhile, those with fewer earnings to tax worry about workers’ rights, wages, and benefits.

Janessa spoke of tensions among people with different experiences. People get divided by race, while those with generations of family history in America are suspicious of more recent immigrants.

Maliya added that citizens who “don’t believe their government is doing the right thing” have staged protests.

“Is that a problem?” I asked.

“I think most of the time it is a good thing,” Maliya replied.

True, said a student named Cory; but protest movements reveal the country’s problems. People protest when they feel their concerns are unheard. He mentioned the Black Lives Matter movement.

I asked, “Does preserving self-government require giving representation and a voice to all citizens?” Van Gaasbeek thought Lincoln could help on this point. He turned the conversation to Lincoln’s Fragment on the Constitution and Union. “Do you remember?” he asks the class. “About the apple?”

Casey remembered Lincoln’s analysis, based on an allusion to a verse from Proverbs—“A word fitly spoken is like apples of gold in pictures of silver.” Lincoln related the “word fitly spoken” to the central promise of the Declaration: that all men are created equal. To Lincoln, the Constitution was a structure of laws created to safeguard this promise. Casey, Van Gaasbeek later told me, was the student who first realized what Lincoln meant.

Now Casey offered a colorful synthesis of Lincoln’s comments on the sectional crisis over slavery: “The apple was like the Declaration, and it was held in place by the framers of the Constitution. But there was a court case about a slave named Dred Scott. And in his ruling, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court said that the enslaved man was not even worth three-fifths of a person. That ruling really threatened the golden apple.”

“Does the Constitution make any sense if we don’t believe in human equality?” I asked. “For example, Casey, why doesn’t Jyair’s vote count for twice as much as your vote?”

“Well, that wouldn’t make sense if all of us are created equal,” Casey responded.

“So, majority rule means everyone’s vote is worth the same as everyone else’s.”

I’d delayed getting to what I really wanted to discuss with the class: Lincoln’s analysis of the most dangerous threats to American democracy. “You’ve read a lot of Lincoln’s writing,” I said. “Your teacher says you read the Lyceum speech that he gave as a young man. Tell me about that.”

Amora said, “He’s criticizing mob rule. He’s saying that if we disagree with a law, we still have to follow it. We can fight to change it, but until it’s changed, we have to follow it. We have to follow the Constitution in order to maintain our independence.”

“When Lincoln speaks of mob rule, what sorts of things does he mean?”

“They were tarring and feathering and hanging people,” Amora recalled.

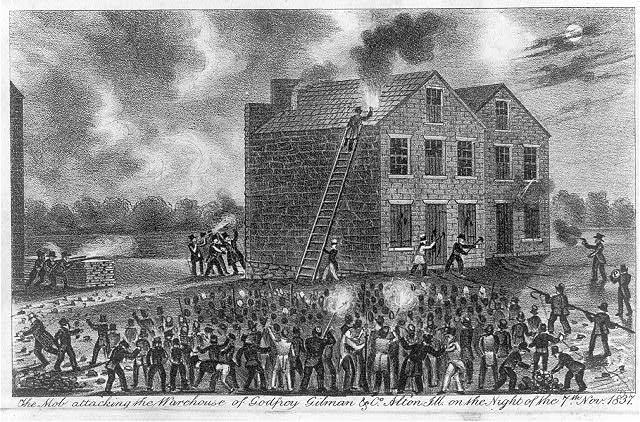

Madisyn added, “There was a newspaper editor saying things they didn’t like, and they threw his printing press in the river.”

Van Gaasbeek recounted the story. “Elijah Lovejoy was an abolitionist newspaper editor. He was printing his anti-slavery message in 1837 in southern Illinois and sending it to Missouri, a slave state. People said, ‘You can’t publish that here!’ So now the rights of Southerners to hold slaves are pitted against freedom of the press. Lincoln argues that no matter what he’s printing, you have no right to break his press—or to shoot him, as they did! And remember, Lincoln also mentions the riverboat gamblers. They were assumed to be swindling people, so a mob took them off a riverboat and hung them. Lincoln says, you can’t do that—we have a court system for a reason. And if there is no law against cheating while gambling, change the laws.”

“Do you all feel that mob rule is a threat today?” I asked.

“Yes!” several students answered.

“January 6, 2021,” DiWash said. “That insurrection was a perfect example of what Lincoln was criticizing 200 years earlier. It was trying to disrupt the peaceful transfer of power provided for by our Constitution.”

“Can you think of any other instances of mob rule occurring today?”

Madisyn said, “Cory mentioned the Black Lives Matter movement. I know we have a right to peaceful assembly, but when protesters start to fight, break into stores, or hurt other people, it goes from being a peaceful protest to rioting—to mob rule.”

“How does that make other citizens feel—say, those who are watching events on TV?”

“They can get scared. If I were to see a protest turn into a riot, it would discourage me from wanting to help the protesters’ cause. I would feel unprotected, and I’d look for someone to protect me.”

“It could lead to the breakdown of democratic institutions,” DiWash added. “Lincoln says a strong man, a tyrant, could take advantage of the situation.”

“Do you guys remember what else Lincoln said?” Van Gaasbeek prompted. “That Americans would not be conquered by a foreign nation . . .”

“—that we could only be conquered by ourselves,” Cory said.

As the period drew to a close, students discussed the reasons for Lincoln’s success as a leader.

“He was moderate,” Cory said. “He could see both sides’ goals, and he wanted to prevent the coming war—” so he tried to persuade the South that war was not in their interest. “I think he was elected because people thought he might be able to lead everyone.”

“But the South didn’t listen. They fired on Fort Sumter anyway,” Van Gaasbeek said.

The bell rang, and students began to gather their books. But DiWash wasn’t finished. “Guys, before we go, I want to say something else. Lincoln got elected because his rhetoric was so good. It was a cut above everyone else’s.”

“I would love to talk with you about that sometime,” I said, as DiWash grabbed his books and hurried to his next class.