Taming the ship of fools

Greta Thunberg accused participants of the 2023 World Economic Forum with ‘fuelling the destruction of the planet’. She argued that the irresponsibility of the economic elite, who ‘are prioritizing self-greed, corporate greed and short-term economic profits’, discredits their alleged competence.

Thunberg, who called for the complete dismissal of their opinion, is also often dealt criticism: in 2020, for example, then US president Donald Trump famously labelled Thunberg as one of ‘the perennial prophets of doom’. This enmity between the economic and political elite and climate activists has deepened ever since. With a constructive compromise seemingly far off, can radical criticism from outside the political elite still have a positive impact on social affairs?

Whose questionable perception?

Trump’s claims evoke a long tradition of controversial Christian apocalypticism within American religious history. Millenarian upheavals have affected most mayor American denominations, including the Baptists, Methodists, Adventists, Mormons, Pentecostals and Jehovah’s Witnesses. End-of-the-world prophecies, which became commonplace yet worn-out in nineteenth-century revivalism, managed to survive the twentieth century in various post-Christian mutations. Some twenty-first century examples include a failed doomsday prediction by the Japanese Aum Shinrikyo (Supreme Truth) cult responsible for the 1995 Tokyo subway Sarin nerve agent attack, the Y2K scare, and the Mayan calendar hoax in 2012. Despite all these warnings, the World did not end.

With these failures in mind, it seems a low-hanging fruit to cast the false-prophet shadow on Thunberg but to do so poses some problems. Thunberg’s ‘apocalypticism’ is not based on numerological calculations, prophecies or revelations but grew out of fact-based predictions. And the criticism she expresses identifies rational causes, her conclusions deriving from them, which should therefore be seen as political criticism and not as millenarian vision.

Thunberg portrays the economic elite’s behaviour in two connected yet differentiated groupings. The first takes a moral to legal shape: from irresponsibility and greed to criminality. ‘As long as they can get away with it, they will continue to invest in fossil fuels, they will continue to throw people under the bus,’ said Thunberg at the WEF. The second recognizes thoughts beyond conscious intentions, charging leaders with a warped mental condition. Thunberg envisions them as people who inadvertently act against their own interest because their concepts of rationality are too narrow. In short, they are either villains or fools, or both.

Early taming of fools

The idea that human society is inescapably approaching an end, and the disaster will be caused by collective incompetence and a total disregard for the common good, has a long history that often appears interwined with religious millenarianism. Records of an imminent social disaster already surface at the dawn of Greek writing in the early sixth century BCE. The remaining fragments of Alcaeus of Mytilene’s ‘ship-of-state’ poems tell of the enormous common effort that is required to steer a ship in a terrible storm and sail it into safe harbour to avoid disaster. Alcaeus’s verse is commonly understood as a political call-to-action for a joint effort to save a collapsing community in times of internal or external menace:

Today, let every man be dedicated.

And may we never cause shame

To our noble parents who lie beneath the earth

This heroic trope was famously expanded upon and turned inside-out by Plato in The Republic. In the dialogue Plato characterizes Socrates cynically comparing the state to a ship, one steered by a hearing-impaired, short-sighted and untrained captain, and manned by quarrelling ignorant sailors who all think they could do better – and also claim their right to do so. The sailors mutiny, intoxicate the captain, take possession of the ship, plunder the cargo and start drinking themselves. Plato plays on raising demand for competence by projecting a ‘true pilot’ who can take control of the chaotic situation:

‘but that the true pilot must pay attention to the year and seasons and sky and stars and winds, and whatever else belongs to his art, if he intends to be really qualified for the command of a ship, and that he must and will be the steerer, whether other people like or not – the possibility of this union of authority with the steerer’s art has never seriously entered into their thoughts or been made part of their calling.’

The necessary emergence of competence and leadership embodied in a single person reveals Plato’s deep scepticism towards the efficiency of Greek democracy as a political institution. He presses the need for charismatic leadership to assume power from self-proclaimed but ignorant and selfish actors, and by a superior insight organizing them into a hierarchy led by the visionary. For Plato this seems to be the only solution to prevent private interest plundering the common good and wrecking the entire system, including the perpetrators themselves. The visionary has to use all available means to tame the fools and save the community.

Renaissance warnings of ignorance

The misguided ship as a metaphor of a self-destructive community in a vacuum of power was picked up and expanded upon during the Renaissance. German humanist and theologian Sebastian Brant’s book Ship of Fools is a typology of over 100 buffoons, constituting the crew and passengers of a vessel sailing to Narragonia. He analyses each vice individually, pointing out how they contribute to failure, merging the line between villains, fools and the reader-observer:

Who thinks that he is not affected

To wise men’s doors be he directed,

There let him wait until mayhap

From Frankfurt I can fetch a cap.

Brant went beyond describing failing morals, expanding the scope by incorporating millenarian warnings based on horoscopic predictions. This crossover between moral satire and doomsday prophecy found a lot of resonance with the late-Medieval European intelligentsia, making Brant’s book one of the most popular publications in the last two decades preceding the Reformation.

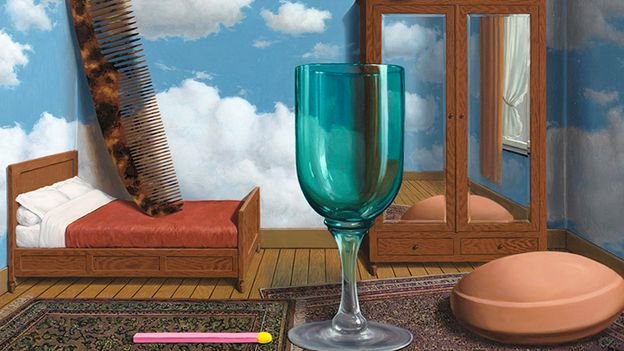

The Ship of Fools, Hieronymus Bosch, c.1450-1516, crop from left wing of triptych. Image via Wikimedia Commons

Brant’s version of the ship-of-fools metaphor supposedly inspired artist Hieronymus Bosch’s Ship of Fools, Erasmus’ social satires and, indirectly, the Reformation, as the theme also surfaces in Luther’s Address to the Christian Nobility from 1520. In this work the fool is the Holy Roman Empire letting the abuses of the Papacy continue without retaliation, leading to the decline of both Church and State. In this case fools and villains are on the opposite side. And the visionary enlightens the fools, warning them about the dangers of their ignorance.

Clerical humanist Faustino Perisauli represents a different blend of the human folly tradition, as he introduces a shared existential-level failure: death itself. In his poem On the Triumph of Folly, he portrays mortality as the root cause of human suffering and the perceptible loss of moral orientation. Referring to the achievements of Alexander the Great he writes:

What now? He has fallen. Tremendous efforts in the thousands

Wither : How many good deeds are sealed under the marble by

Death, the housekeeper of the Little World.

By unifying all humans in the common experience of death, the impetus for improvement or change seems to suffer to the point of nihilism with religion providing the only consolation.

Perisauli is particularly suspicious of the arts and sciences, declaring them useless and empty. As a nineteenth century commentator summarises his stance:

‘There is no doubt that it is all true what he says about the vanity of human labour, and the failure of every human life, and that fame, however long it be, does no good, and that in general a living dog is better than a dead lion, unless maybe for museum purposes.’

Perisauli’s poetry seems to be a marriage of ‘Memento Mori’ and ‘Vanitas’ traditions. In his case being the fool is not realizing the hopelessness of any action. And the visionary’s sole role is to reveal the inevitability of earthly despair. This kind of doom-mongering seems paralyzing, as no action can improve the situation. Perisauli’s work is often associated with Erasmus’ In Praise of Folly, although their relationship is obscure as Erasmus’s book appeared earlier in print.

Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa appears to be in the same boat as Faustino in his On the Uncertainty and Vanity of the Arts and Sciences. This grand tour de force against learned knowledge seems to ride on the anti-intellectual ‘sola scriptura’ waves of the Reformation defaming everything beyond belief:

And it behoves us to shew how intolerable the blindness of Men is, to wander from the truth, misguided by so many Sciences and Arts and by so many Authors and Doctors thereof. For how great a boldness is it, what an arrogant presumption, to prefer the Schools of philosophers before the Church of Christ? and to extol or equal the Opinions of Men, to the Word of God?

Agrippa’s sinister staging undermines the value of knowledge in society, raising the role of faith above reason. Being an experienced mercenary, courtier, lecturer and occult encyclopaedist, his religious fervour puzzled researchers just as much as his criticism against occultism, his own field of expertise. Agrippa’s work looks more like a market-centred publishing enterprise to make profit on growing anti-intellectual sentiments due to the ongoing Reformation than a sincere Pauline conversion.

Escaping the raging storm

One last example of the twists and turns of the ship-of fools metaphor comes from Robert Fludd’s first book Apologia compendiaria… from 1616, commonly referred to as Defence of the Rosicrucians. Being a Paracelsian doctor and alchemical author, Fludd embodied a special blend of the late-Renaissance Protestant intellectual, the occult encyclopaedist and the Royalist entrepreneur. His version of apocalyptic rhetoric comes in a particularly Calvinist form:

After contemplating day and night over the disasters of our current lives, which seldom finish to torture us before the blessed death comes, I came to the conclusion that the journey of mortals on this Earth can be well likened to a sea upset by raging stormy waves, upon which our body is like an aimlessly drifting ship constantly threatened by the deadly waves; and the soul is like a captain unaware of the rules of his craft, trying to steer his vessel towards the harbour of happiness with hopeful wishes, having no idea where it resides.

Fludd’s personal tone adds an introverted focus to blend the tropes of previous narratives: misery, loss of guidance, lack of vision, and the hopeless desire for the harbour of happiness. Common goals are lost, people are clueless on the widest scale and they can only blame themselves.

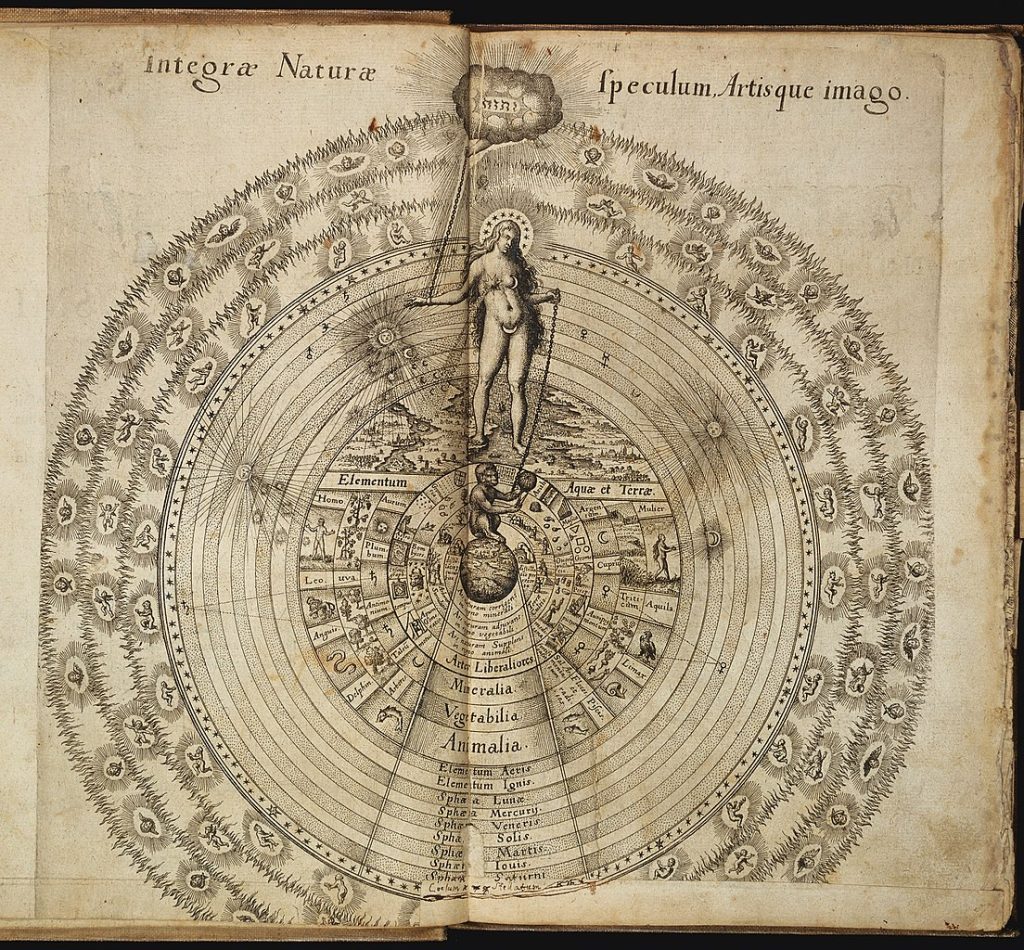

The great chain from God to nature and from nature to man. Robert Fludd, Utriusque cosmi maioris scilicet…1617-1618. Image via Wellcome Trust, Wikimedia Commons

Beyond Fludd’s well-established introduction, his solution to the situation takes on a more innovative form. Following then popular alchemical astrology, he claimed that the world is in chaos because astrological constellations had entered the age of fire. Although his thesis seemingly supports the notion of imminent apocalypse for most perennial ‘prophets of doom’, following the Rosicrucian manifestos – the first major, large-scale intellectual hoax of the Early Modern period – Fludd provided a different interpretation. In his Protestant-alchemical synthesis, the progression of fire on Earth relates to an increased presence of God and, therefore, to intellectual enlightenment. The Rosicrucians may have failed to realize his hopes, but the programme, to some extent, gradually unfolded a century later with the Enlightenment.

Breakthrough or parallel reality?

The ship-of-fools metaphor has taken many different forms from Plato to Fludd. Without proposing that the above snapshots describe a continuous process, it is interesting to see the positioning of folly and its corrective chances through different contexts. In the case of Plato and Brant, folly and vice were positioned as surmountable hindrances: the cure was true leadership for Plato and moral improvement for Brant. However, in the stance of Perisauli, this optimism seems to be broken: folly becomes a basic human condition compared to death, which cannot be overcome, only accepted. Knowledge becomes folly, ambition turns into vanity. Hope for improvement or corrective measures are lost. Only consolation can cure the reckless soul. Agrippa’s attack on the sciences takes over this anti-intellectual sentiment from Perisauli but replaces passive acceptance with the enthusiasm of a revivalist, albeit a doubtful one. And, finally, Fludd, who incorporated most previous attitudes, presented his solution as an escapist fantasy into a world constructed of the occult tradition and an imagined Rosicrucian reform that never materialized.

Within these various contexts, the position and function of ‘prophets of doom’ vary greatly. Where there is belief in the possibility of change and action, the visionary takes an active role in perfecting a malfunctioning system. However, if the personal horizon of the critic is closed and a practical breakthrough does not seem to be possible, apocalyptic warnings lead to internal travel and an escape into a parallel reality.

The reputation of critics, whistleblowers or doom mongers seems to be constituted by their relationship to driving change, but also their potential impact. In a closed system where the future is inevitably determined by the preconditions, Thunberg and fellow activists are predestined to take a passive-aggressive role without any potential impact. However, should the potential for change open up, warnings and criticism may contribute to a collective solution.