Occupied futures | Eurozine

As the object of study rather than the subject of communication, the so-called Middle East has long been a locus for advanced technologies of mapping. In the field of aerial vision, these technologies historically employed cartographic and photographic methods. The legacy of cadastral, photographic and photogrammetric devices continues to impact how people and regions are quantified, nowhere more so than when we consider the all-encompassing, calculative gaze of autonomous systems of surveillance. Perpetuated and maintained by Artificial Intelligence (AI), these remotely powered technologies herald an evolving era of mapping that is increasingly implemented through the operative logic of algorithms.

Algorithmically powered models of data extraction and image processing have, furthermore, incrementally refined neo-colonial objectives: while colonization, through cartographic and other less subtle means, was concerned with wealth and labour extraction, neo-colonization, while still pursuing such objectives, is increasingly preoccupied with data extraction and automated models of predictive analysis. Involving as it does the algorithmic processing of data to power machine learning and computer vision, the functioning of these predictive models is indelibly bound up with, if not encoded by, the martial ambition to calculate, or forecast, events that are yet to happen.

As a calculated approach to representing people, communities and topographies, the extraction and application of data is directly related to computational projection: ‘The emphasis on number and the instrumentality of knowledge has a strong association with cartography as mapping assigns a position to all places and objects. That position can be expressed numerically.’ If a place or object can be expressed numerically, it bestows a privileged command on to the colonial I/eye of the cartographer. This positionality can be readily deployed to manage – regulate, govern and occupy – and contain the present and, inevitably, the future.

These panoptic and projective ambitions, initially embodied in the I/eye of the singular embodied figure of the cartographer, nevertheless need to be automated if they are to remain strategically viable. To impose a perpetual command entails the development of increasingly capacious models of programmed perception. Established to support the aspirations of colonialism and the imperatives of neo-colonial military-industrial complexes, contemporary mapping technologies – effected through the mechanized affordances of AI – extract and quantify data in order to project it back onto a given environment. The overarching effect of these practices of computational projection is the de facto expansion of the all-seeing neo-colonial gaze into the future.

The evolution of remote, disembodied technologies of perpetual surveillance, drawing as they did upon the historical logic and logistics of colonial cartographic methods, also necessitated the transference of sight – the ocular-centric event of seeing and perception – to the realm of the machinic. The extractive coercions and projective compulsions of colonial power not only saw the entrustment of sight to machinic models of perception but also summoned forth the inevitable automation of image production. It is within the context of Harun Farocki’s ‘operational images’, by way of Vilém Flusser’s theorization of ‘technical images’, that we can link the colonial ambition to automate sight with the role performed by AI in the extractive pursuits of neo-colonialism.

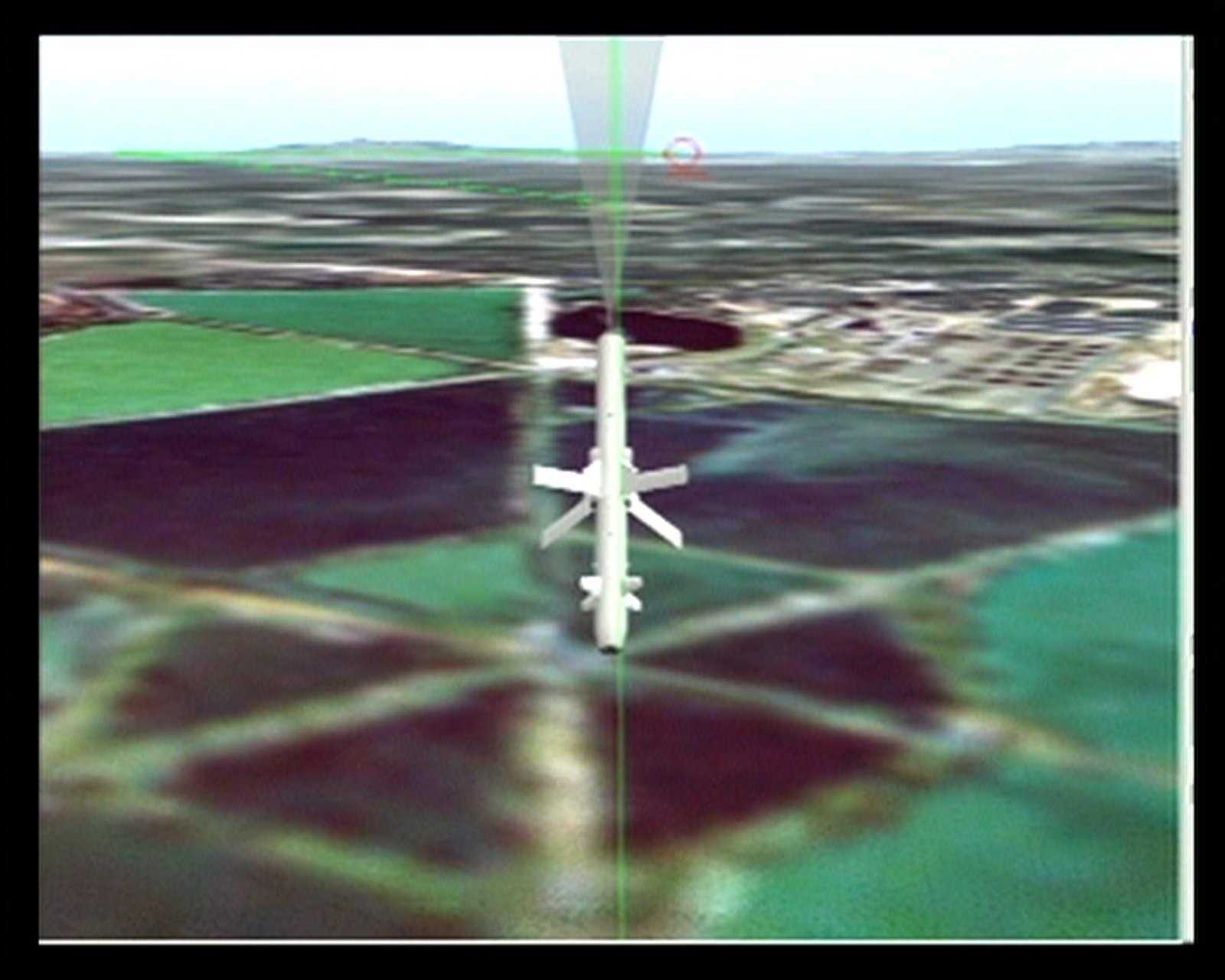

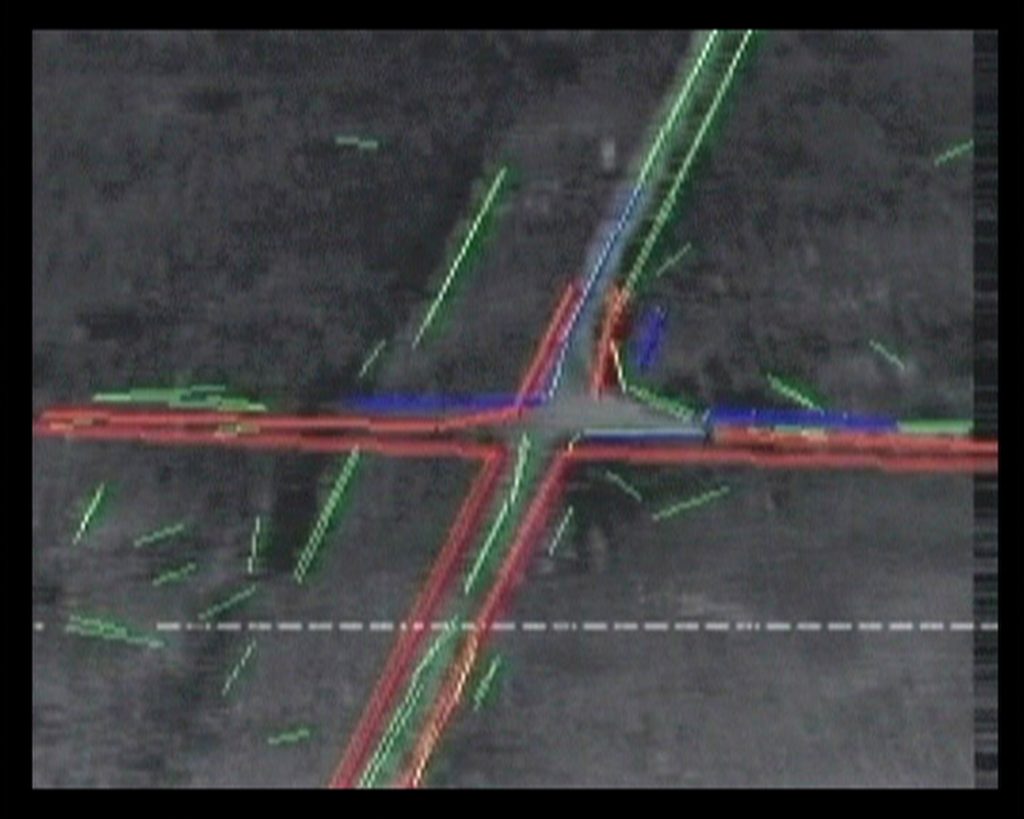

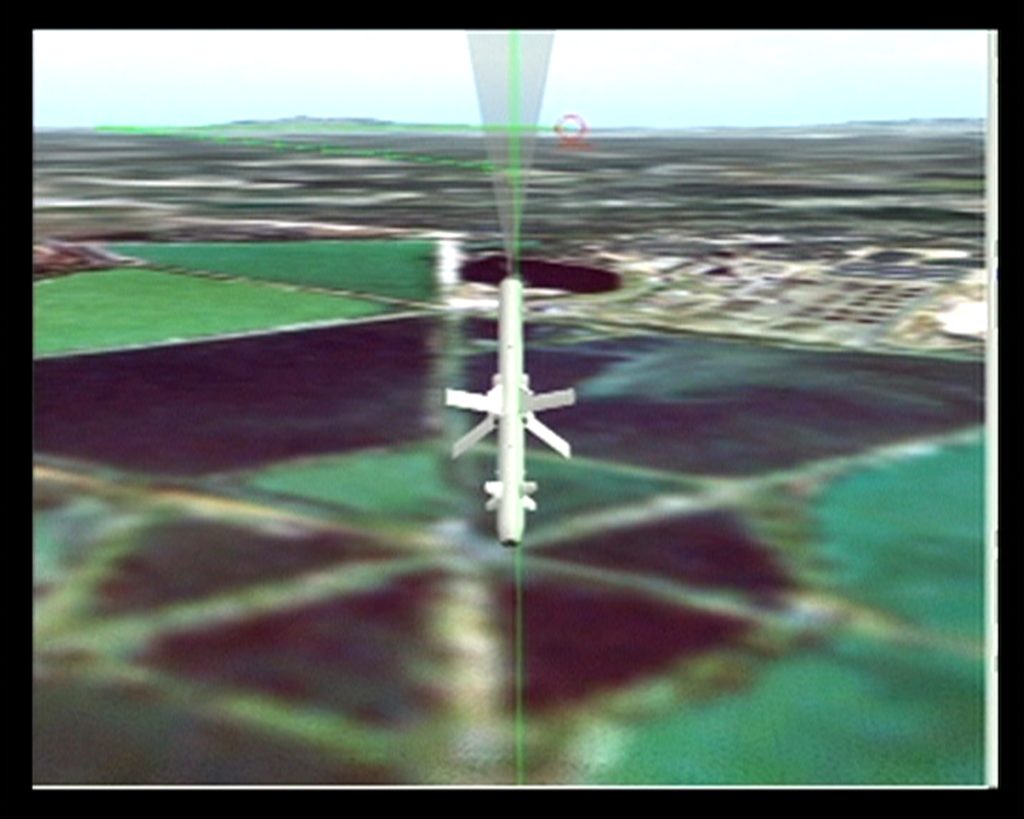

Harun Farocki, Eye Machine III, © Harun Farocki, 2003. Image via Springerin

Based as they are on alignments within processes of automation, mining, quantifying and archiving, ‘technical images’ and ‘operational images’ foreshadow methods of data retrieval, storage and targeting, which are now associated with the algorithmic apparatuses that power Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV) and Lethal Autonomous Weapons (LAW). When we consider the relationship between ‘technical images’ and ‘operational images’, in the context of the devolution of ocular-centric models of vision and automated image processing, we can also more readily recognize how the deployment of AI in UAVs and LAWs propagates an apparatus of dominion that both contains and suspends the future, especially those futures that do not serve the imperatives of neo-colonization.

Projecting ‘thingification’

Understood as a system that demonstrates non-human agency, for Flusser an apparatus essentially ‘simulates’ thought and, via computational processes, enables models of automated image production to emerge. The ‘technical image’ is, accordingly, ‘an image produced by apparatuses’ – the outcome of sequenced, recursive computations rather than human-centric activities. ‘In this way,’ Flusser proposed, ‘the original terms human and apparatus are reversed, and human beings operate as a function of the apparatus.’ It is the sense of an autonomous machinic functioning behind image production that informs Harun Farocki’s seminal account of the ‘operational image’.

Void of aesthetic context, ‘operational images’ are part of a machine-based operative logic and do not, in Farocki’s words, ‘portray a process but are themselves part of a process.’ Indelibly defined by the operation in question, rather than any referential logic, these images are not propagandistic (they do not try to convince), nor are they levelled towards the ocular-centric realm of human sight (they are not, for example, interested in directing our attention). Inasmuch as they exist as abstract binary code rather than pictograms, they are likewise not imagistic – in fact, they are not even images: ‘A computer can process pictures, but it needs no pictures to verify or falsify what it reads in the images it processes.’ Reduced to numeric code, ‘operational images’, in the form of sequenced code or vectors, remain foundational to the development of contemporary models of recursive machine learning and computer vision.

In the final part of Farocki’s Eye/Machine trilogy (2001–2003) there is a conspicuous focus on the non-allegorical, recursively relayed image – the ‘operational image’ – and its role in supporting contemporary models of aerial targeting. In direct reference to the first Gulf War in 1991, and the subsequent invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq in 2001 and 2003, Farocki observed that a ‘new policy on images’ had ushered in a paradigm of opaque and largely unaccountable methods of image production that would inexorably inform the future of ‘electronic warfare’. The novelty of the operational images in use in 2003 in Iraq, it has been argued, was to be found in the ‘fact that they were not originally intended to be seen by humans but rather were supposed to function as an interface in the context of algorithmically controlled guidance processes.’ Accordingly, ‘operational images’, based as they are on numeric values, insular processes and a series of recursive instructions, can be understood in algorithmic terms: they effect discrete, autonomous procedures – related to targeting in particular – from within so-called ‘black box’ apparatuses. Despite the opacities involved in their methods, however, the consequences of ‘operational images’ in contemporary theatres of warfare is repeatedly revealed in their real world impact. Deployed in ‘algorithmically controlled guidance processes’ they are, in sum, routinely utilized to kill people.

Harun Farocki, Eye Machine III, © Harun Farocki, 2003. Image via Springerin

Through locating the epistemological and actual violence that impacts communities and individuals who are captured, or ‘tagged’, by autonomous systems, we can further reveal the extent to which the legacy of colonialism informs the algorithmic logic of neo-colonial imperialism. The logistics of data extraction, not to mention the violence perpetuated as a result of such activities, is all too amply captured in Aimé Césaire’s succinct phrase: ‘colonisation = thingification’. Through this resonant formulation, Césaire highlights both the inherent processes of dehumanization practised by colonial powers and how, in turn, this produced the docile and productive – that is, passive and commodified – body of the colonized.

As befits his time, Césaire understood these configurations primarily in terms of wealth extraction (raw materials) and the exploitation of physical, indentured labour. However, his thesis is also prescient in its understanding of how colonization seeks unmitigated control over the future, if only to pre-empt and extinguish elements that did not accord with the avowed aims and priorities of imperialism: ‘I am talking about societies drained of their essence, cultures trampled underfoot, institutions undermined, lands confiscated, religions smashed, magnificent artistic creations destroyed, extraordinary possibilities wiped out.’ The exploitation of raw materials, labour and people, realized through the violent projections of western knowledge and power, employed a process of dehumanization that deferred, if not truncated, the quantum possibilities of future realities.

Predicting ‘unknown unknowns’

In the context of the Middle East, the management of risk and threat prediction – the containment of the future – is profoundly reliant on the deployment of machine learning and computer vision, a fact that was already apparent in 2003 when, in the lead up to the invasion of Iraq, George W. Bush announced that ‘if we wait for threats to fully materialize, we will have waited too long.’ Implied in Bush’s statement, whether he intended it or not, was the unspoken assumption that counter-terrorism would be necessarily aided by semi if not fully-autonomous weapons systems capable of maintaining and supporting the military strategy of anticipatory and preventative self-defence. To predict threat, this logic goes, you have to see further than the human eye and act quicker than the human brain; to pre-empt threat you have to be ready to determine and exclude (eradicate) the ‘unknown unknowns’.

Although it has been a historical mainstay of military tactics, the use of pre-emptive, or anticipatory, self-defence – the so-called ‘Bush doctrine’ – is today seen as a dubious legacy of the attacks on the US on 11 September 2001. Despite the absence of any evidence related to Iraqi involvement in the events of 9/11, the invasion of Iraq in 2003 – to take but one particularly egregious example – was a pre-emptive war waged by the US and its erstwhile allies in order to mitigate against such attacks in the future.

Harun Farocki, Eye Machine III, © Harun Farocki, 2003. Image via Springerin

In keeping with the ambition to predict ‘unknown unknowns’, Alex Karp, the CEO of Palantir, wrote an opinion piece for The New York Times in July 2023. Published 20 years after the invasion of Iraq, and therefore written in a different era, the apparent threats to US security and the need for robust methods of pre-emptive warfare, were in the forefront of Karp’s thinking, nowhere more so than when he espoused the seemingly prophetic if not oracle-like capacities of AI predictive systems.

Conceding that the use of AI in contemporary warfare needs to be carefully monitored and regulated, he proposed that those involved in overseeing such checks and balances – including Palantir, the US government, the US military and other industry-wide bodies – face a choice similar to the one the world confronted in the 1940s. ‘The choice we face is whether to rein in or even halt the development of the most advanced forms of artificial intelligence, which some argue may threaten or someday supersede humanity, or to allow more unfettered experimentation with a technology that has the potential to shape the international politics of this century in the way nuclear arms shaped the last one.’

Admitting that the most recent versions of AI, including the so-called Large Language Models (LLMs) that have become increasingly popular in machine learning, are impossible to understand for user and programmer alike, Karp accepted that what ‘has emerged from that trillion-dimensional space is opaque and mysterious’. It would nevertheless appear that the ‘known unknowns’ of AI, the professed opacity of its operative logic (not to mention the demonstrable inclination towards erroneous prediction, or hallucinations), can nevertheless predict the ‘unknown unknowns’ associated with the forecasting of threat, at least in the sphere of the predictive analytics championed by Palantir. Perceiving this quandary and asserting, without much by way of detail, that it will be essential to ‘allow more seamless collaboration between human operators and their algorithmic counterparts, to ensure that the machine remains subordinate to its creator’, Karp’s overall argument is that we must not ‘shy away from building sharp tools for fear they may be turned against us’.

This summary of the continued dilemmas in the applications of AI systems in warfare, including the peril of machines that turn on us, needs to be taken seriously insofar as Karp is one of the few people who can talk, in his capacity as the CEO of Palantir, with an insider’s insight into their future deployment. Widely seen as the leading proponent of predictive analytics in warfare, Palantir seldom hesitates when it comes to advocating the expansion of AI technologies in contemporary theatres of war, policing, information management and data analytics more broadly. In tune with its avowed ambition to see AI more fully incorporated into theatres of war, its website is forthright on this matter. We learn, for example, that ‘new aviation modernization efforts extend the reach of Army intelligence, manpower and equipment to dynamically deter the threat at extended range. At Palantir, we deploy AI/ML-enabled solutions onto airborne platforms so that users can see farther, generate insights faster and react at the speed of relevance.’ As to what reacting ‘at the speed of relevance’ means we can only surmise this has to do with the pre-emptive martial logic of autonomously anticipating and eradicating threat before it becomes manifest.

Palantir’s stated objective to produce predictive models and AI solutions that enable military planners to (autonomously or otherwise) ‘see farther’ is not only ample corroboration of its reliance on the inferential, or predictive, qualities of AI but, given its ascendant position in relation to the US government and the Pentagon, a clear indication of how such neo-colonial technologies will determine the prosecution and outcomes of future wars in the Middle East. This ambition to ‘see farther’, already manifest in colonial technologies of mapping, also supports the neo-colonial ambition to see that which cannot be seen – or that which can only be seen through the algorithmic gaze and its rationalization of future realities. As Edward Said argues in his seminal volume Orientalism, the function of the imperial gaze – and colonial discourse more broadly – was ‘to divide, deploy, schematize, tabulate, index, and record everything in sight (and out of sight)’. This is the future-oriented algorithmic ‘vision’ of a neo-colonial world order – an order maintained and supported by AI apparatuses that seek to quarter, appropriate, realign, predict and record everything in sight – and, critically, everything out of sight.

Digital imperialism

Although routinely presented as an objective ‘view from nowhere’ (a strategy used in colonial cartography), AI-powered models of unmanned aerial surveillance and autonomous weapons systems – given the enthusiastic emphasis on extrapolation and prediction – are epistemic structures that produce realities. These computational structures, provoking as they do actual events in the world, can also be used to justify the event of real violence. For all the apparent viability, not to mention questionable validity, of the AI-powered image processing models deployed across the Middle East, we need to therefore observe the degree to which ‘algorithms are political in the sense that they help to make the world appear in certain ways rather than others. Speaking of algorithmic politics in this sense, then, refers to the idea that realities are never given but brought into being and actualized in and through algorithmic systems.’ This is to recall that colonization, as per Said’s persuasive insights, was a ‘systematic discipline by which European culture was able to manage – and even produce – the Orient politically, socially, militarily, ideologically, scientifically, and imaginatively during the post-Enlightenment period.’ The fact that Said’s insights have become largely accepted if not conventional should not distract us from the fact that the age of AI has witnessed an insidious re-inscription of the racial, ethnic and social determinism that figured throughout imperial ventures and their enthusiastic support for colonialism.

Carmel of southern Palestine, photographed between 1950 and 1977, Matson (G. Eric and Edith) Photograph Collection, Library of Congress. Image via Springerin

In the milieu of so-called Big Data, machine learning, data scraping and applied algorithms, a form of digital imperialism is being profoundly, not to mention lucratively, programmed into neo-colonial prototypes of drone reconnaissance, satellite surveillance and autonomous forms of warfare, nowhere more so than in the Middle East, a nebulous, often politically concocted, region that has long been a testing ground for Western technologies. In suggesting that the machinic ‘eye’, the ‘I’ associated with cartographic and other methods of mapping, has evolved into an unaccountable, detached algorithmic gaze is to highlight, finally, a further distinction: the devolution of deliberative, ocular-centric models of seeing and thinking to the recursive realm of algorithms reveals the callous rendering of subjects in terms of their disposability or replaceability, the latter being a key feature – as observed by Césaire – of colonial discourse and practice.

In light of these computational complicities and algorithmic anxieties, the detached apparatuses of neo-colonization, we might want to ask whether there is a correlation between automation and the disavowal of culpability: does the deferral of perception, and the decision-making processes we associate with the ocular-centric domain of human vision, to autonomous apparatuses guarantee that we correspondingly reject legal, political and individual responsibility for the applications of AI? Has AI, in sum, become an alibi – a means to disavow individual, martial and governmental liability when it comes to algorithmic determinations of life and, indeed, death?