How a biochemistry department used redacted job applications to achieve gender parity

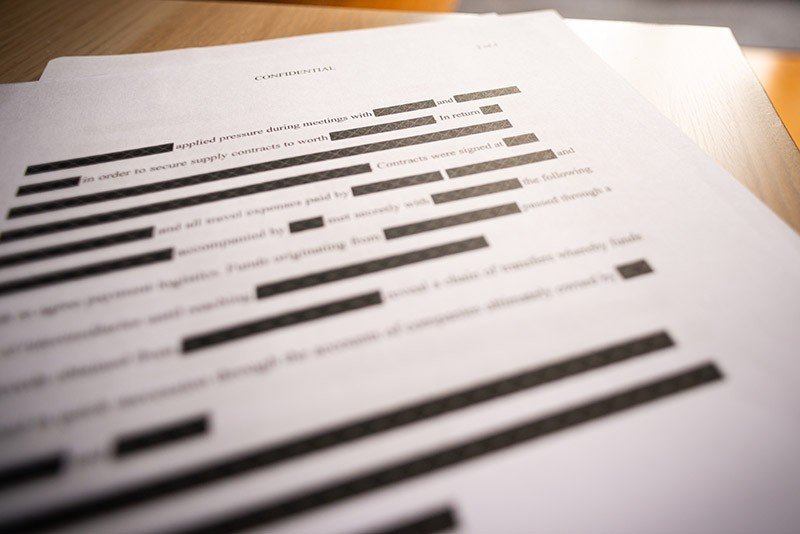

Concealing some of the information on job applications led to more women being hired.Credit: Christopher Ames/Getty

In 2017, when Sherri Christian returned to her institution after a year-long sabbatical, she looked around the biochemistry department and realized that she was the last female hire, seven years earlier. At the time, there were 19 members, just 6 of them women, including her.

During her sabbatical, Christian attended a talk about diversity and inclusion at a Canadian Society for Immunology meeting at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada. Inspired by what she learnt, Christian and her colleagues set about making hiring diversity a priority.

By this year, her department at the Memorial University of Newfoundland Faculty of Medicine in St John’s, Canada, had managed to achieve gender parity. The changes made to hiring processes are described in a preprint posted to the bioRxiv server last month1. It has not been peer reviewed.

Christian’s department is not alone in taking action to boost gender diversity among their staff. In 2022, leaders of several departments at the University of Melbourne, Australia, reported the details of affirmative-action recruitment initiatives that led to more female hires.

And this year, the Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands revealed the results of a five-year policy stating that only female applicants would be considered for permanent academic roles during the first six months of recruitment. The controversial policy led to 50% of all new hires being women, up from 30% previously.

Loneliness

When the Newfoundland project started in 2020, Christian was the only woman to have been hired in ten years. “It was a bit lonely,” she says. “You’d look around and there’d be no women on the committee you are sitting in, or it would be the same other person over and over again because there are only so many people to choose from.”

Between 2020 and 2024, the department’s job postings emphasized the equity, diversity and inclusion aspects of the application process for entry-level tenure-track faculty positions.

But the main change was anonymizing job applications in an attempt to stamp out implicit bias on search committees.

Committee members were given copies of application documents in which candidates’ names and contact information were redacted, as were references to their institution, country and leaves of absence. Gender, religion, ethnicity, race, age and nationality were also removed. This task was done by the head of the department, Mark Berry, who was not involved in evaluating candidates. His work took, on average, 90 minutes per application.

The degree type and year of completion remained, as did the location and title of any national or international conference presentations. Publication titles, including the year of publication and journal, also remained. Berry also added candidates’ authorship position in the publications and presentations.

The redacted versions were then used to draw up a shortlist of around ten candidates for each of the five roles being filled during the study period.

At that point, the full, unredacted applications, as well as reference letters, were supplied to the search committee, enabling members to check that no candidate had been unfairly disadvantaged by any redactions.

One member, for example, said the unredacted version enabled them to see the full extent of one candidate’s outreach activity, which had been redacted because much of it was focused on women in science.

Three or four candidates were then invited to interview. The number of group and one-to-one meetings over the typically two-day process was reduced to decrease applicants’ stress and fatigue. Interviewees were invited to meet with a realtor to discuss housing and living costs.

Biased

The authors found the redactions led to a “substantial difference” in the number of female candidates offered positions. They compared the genders of candidates interviewed and hired for five jobs between 2010 and 2020, and between 2021 and 2024. All five went to women during the study, compared with just one during the earlier period. The move achieved gender parity in the department.

Berry says that the search committee’s members responded positively to the redacted documentation, which enabled them to focus on the application. “They weren’t constantly having to tell themselves not to be biased, they could just relax and turn the brain off and focus on the important stuff,” he adds.

To rule out the possibility that the selection committee was favouring women over others who were the best person for the job, the team also looked at the success rates of the employed candidates in competitive national funding calls. These matched or exceeded expectations. “Thus, our intervention was very successful,” Christian and her colleagues write.

“This is an important and promising study,” says Lisa Kewley, an astronomer at the Harvard and Smithsonian Centre for Astrophysics in Massachusetts. Last year, Kewley and colleagues announced that the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for All Sky Astrophysics in 3 Dimensions, an Australian astronomy research centre that she had co-founded, had achieved gender parity after a five-year programme of education and affirmative action. In early 2018, 38% of the centre’s roughly 150 personnel were women. But by 2023, half of its more than 300 personnel were women.

She says there is more evidence that suggests anonymizing applications for processes such as music auditions and telescope time proposals leads to the selection of candidates that are representative of the applicant pool. “This study shows that these types of anonymization can be applied to academia, something that is often stated is going to be impossible,” she adds.

But she stresses the sample size is small, and a larger study is required to better evaluate the procedure fully. “If other departments followed a similar process, then data from each of those could be collected,” she adds.

Aikaterini Fotopoulou, a neuropsychologist at University College London, says that the small scale of the project works in its favour. Fotopoulou, who runs an institute designed to enshrine inclusivity in all aspects of neuroscience and psychology research, says that often the best way to achieve change is not by big projects, but by “small, specific, localized but impactful action”.

Sarah Laframboise, who heads up Evidence for Democracy, a grass-roots organization in Ottawa that advocates for the use of science in policy decisions, adds that small projects also create the momentum needed for broader institutional changes. “It sets a valuable example that can inspire other departments and institutions to take similar steps,” she adds.