The Global Internet Is Coming Apart

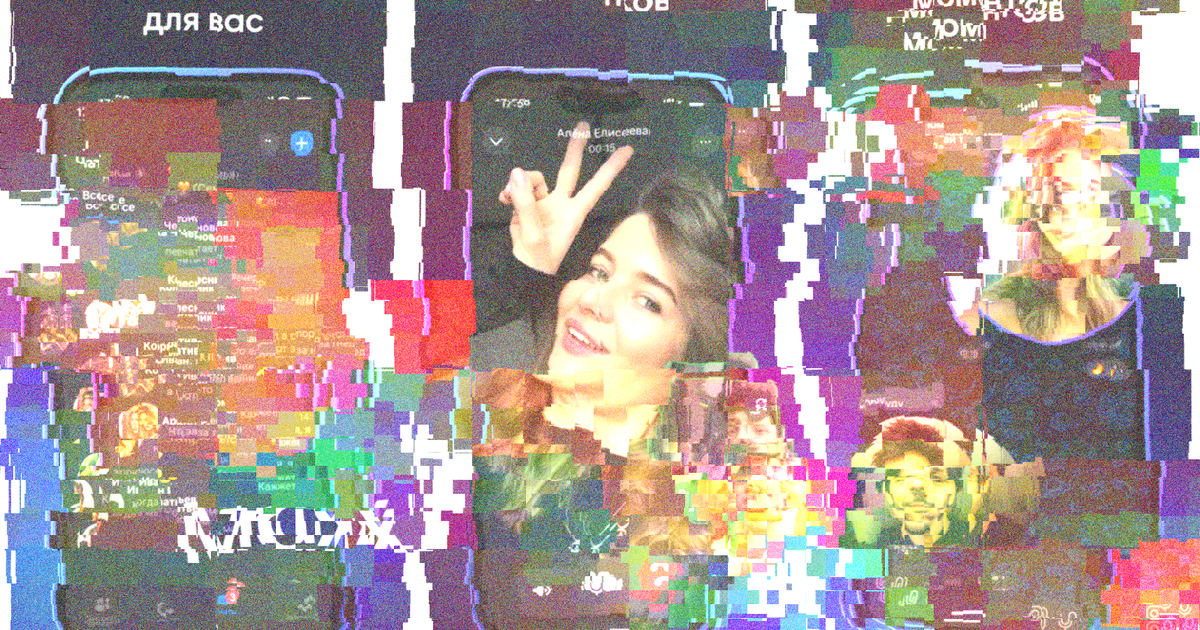

Photo-Illustration: Intelligencer; Graphic: MAX/Apple

The early rise of the internet is usually told as an extension of globalization. New networking technology made instantaneous communication possible, complementing and accelerating international commerce and cultural exchange. As in the rest of the world economy, the U.S. was unusually influential online, exporting not just technology but culture and political norms with it.

The alternative story of the rise of the internet was exemplified by China, which limited the reach of western tech companies, maintained strict control over its domestic networks, and started building a parallel internet-centric economy of its own. And contra western reporting suggesting that this was purely an exercise in isolationism and control, in 2025, the international influence of the Chinese internet and tech companies — even here, as evidenced by the growth and semi-seizure of TikTok — is enormous.

In that context — and the context of America’s renewed trade war — it shouldn’t be surprising that more countries are taking a second look at digital sovereignty and that the global internet as we knew it is pulling apart. Russia, which has a long history of internet censorship and state-aligned tech companies, has taken the extraordinary recent step of interfering with access not just to WhatsApp but also Telegram, the messaging app founded by Pavel Durov, a creator of VK, Russia’s Facebook alternative, who left the country more than a decade ago. The throttling coincided with the launch of MAX, a new government-controlled everything app — basically a messaging app with other features layered on top, modeled on China’s Weixin — and an all-out marketing campaign to get people to switch. “Billboards are trumpeting it. Schools are recommending it. Celebrities are being paid to push it. Cellphones are sold with it preloaded,” the Times reports.

Russia’s obviously in an … unusual diplomatic position these days, but you can hear a version of its stated position — We should have our own big internet platforms as well as greater control over and access to what people do on them — coming from all over the world. (Indeed, the American government’s rationale for the TikTok deal can be understood as a defensive version of the same argument.) In India, the government is talking more openly about favoring homegrown apps for economic and security reasons and highlighting its own domestic “super-app.” From the Financial Times:

A chorus of top Indian officials in recent weeks have publicly backed a domestically developed messaging platform, as the country tries to project its ability to create a homegrown rival to US-developed apps. “Nothing beats the feeling of using a Swadeshi [locally made] product,” [Minister of Commerce] Piyush Goyal wrote on X, adding: “So proud to be on Arattai, a Made in India messaging platform.”

In the aughts, fights over digital globalization were about search engines and popular websites; in the 2010s, they were largely about social networks. Now, they’re about messaging apps, which are different in a number of ways. A lot of messaging traffic is private communication on services like Meta-owned WhatsApp — one of the most popular apps in India, which is WhatsApp’s largest market. Messages on the platform are encrypted by default, meaning that even governments with extensive surveillance capabilities can’t easily see what people are using them for.

China’s Weixin, which operates internationally as WeChat, demonstrates two tantalizing possibilities for other governments: It’s aligned with the state and surveillable; also, as it grew popular and expanded its ambitions, it became the default interface for shopping, banking, media consumption, and interacting with other businesses. This sort of everything app — which American tech executives have openly lusted after, most recently and explicitly Elon Musk — is appealing to tech companies and governments alike for its total centralization. MAX’s goals are clear, with messaging, calls, ID functionality, and plans to allow users to “connect with government services, make doctors’ appointments, find homework assignments, and talk to local authorities.”

The looming segmentation of what we colloquially call the “internet” into various national, nationalist, and perhaps compromised messaging apps leaves governments without such ambitions in an awkward position. The European Union, citing some of the same concerns as the Russian and Indian governments — although mostly focusing on child protection — is considering, against widespread opposition from its citizenry and foreign tech companies alike, “chat control” legislation, which would require tech firms to allow messages to be scanned by authorities for offending content. The EU has some leverage here, of course — nobody wants to lose access to such a large and wealthy market — but tech companies based elsewhere insist that such a requirement is impossible to implement without fundamentally breaking their services or violating user privacy. Under the narrower auspices of stopping online sexual abuse, in other words, the EU is asking — or wishing — for a limited version of the same power China wanted when it made onerous demands of American tech companies in the 2010s, preventing them from entering its market: to regulate and control influential applications that have, up until this point, mostly come from somewhere else.

Taken together, this looks an awful lot like a global shift in how most governments — and their citizens — approach the internet: not as an intrinsically and necessarily global project but as a source of domestic power to be cultivated, protected, and protected against.