How far away are the stars?. For thousands of years, humanity had no… | by Ethan Siegel | Starts With A Bang! | Feb, 2024

For thousands of years, humanity had no idea how far away the stars were. In the 1600s, Newton, Huygens, and Hooke all claimed to get there.

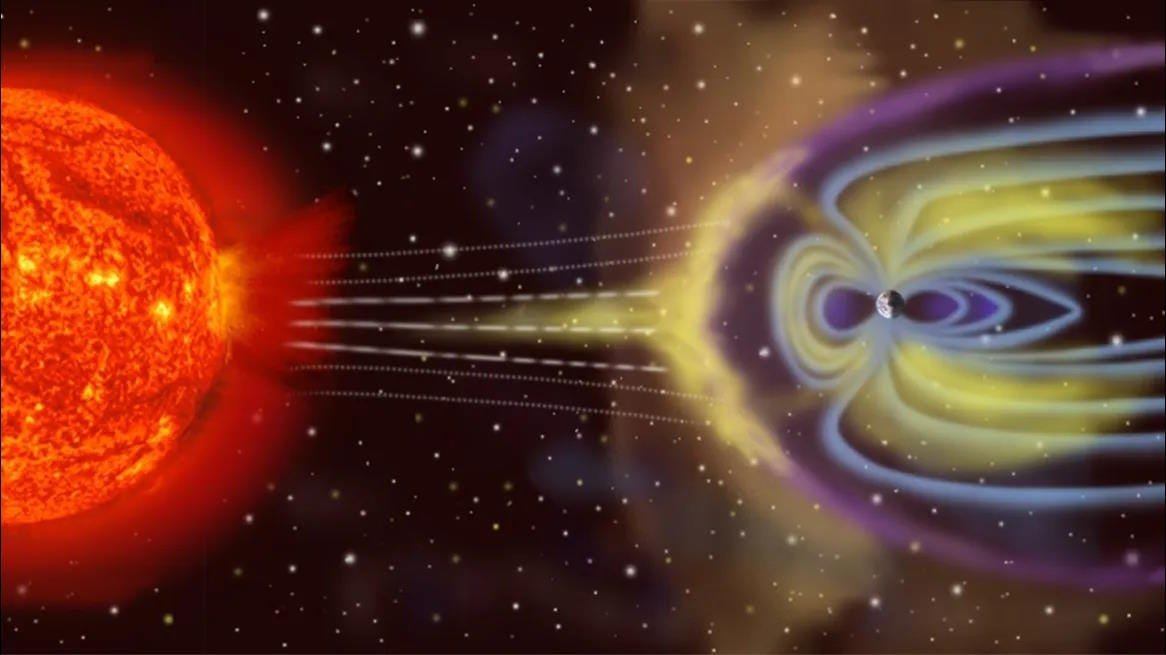

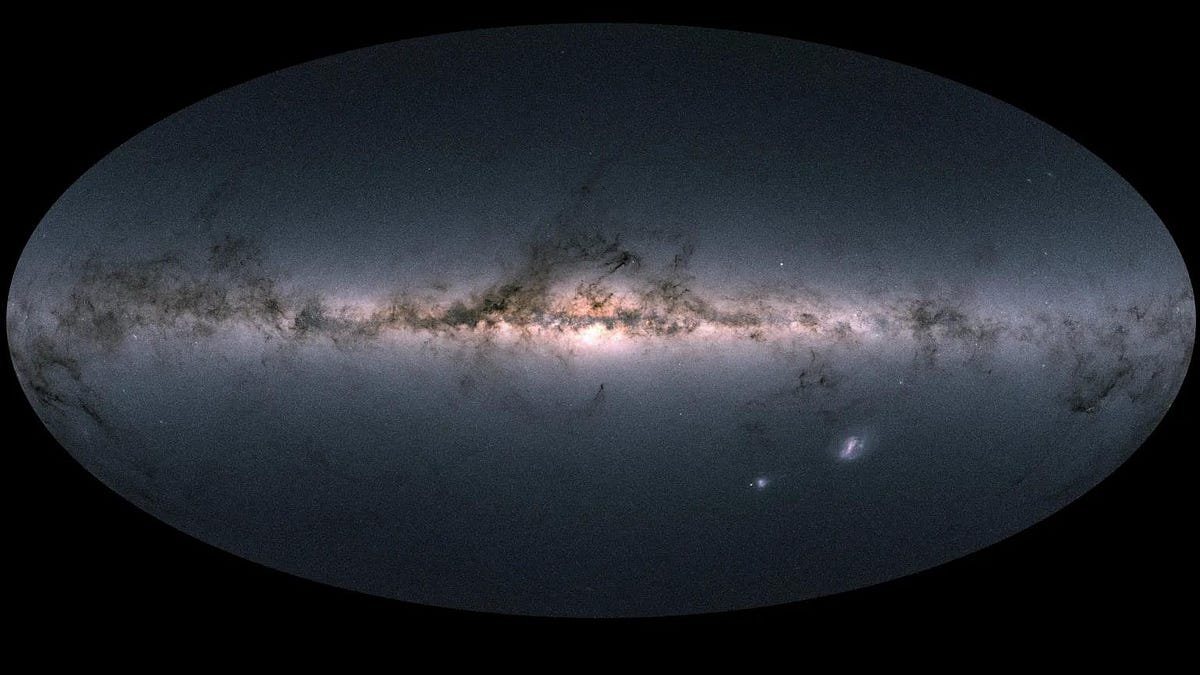

Out there in space, blazing just a scant 150 million kilometers away lies the brightest and most massive object in our Solar System: the Sun. Shining hundreds of thousands of times as bright in Earth’s skies as the next brightest object, the full Moon, the Sun is unique among Solar System objects for producing its own visible light, rather than only appearing illuminated because of reflected light. However, the thousands upon thousands of stars visible in the night sky are all also self-luminous, distinguishing themselves from the planets and other Solar System objects in that regard.

Unlike the planets, Sun, and Moon, the stars appear to remain fixed in their position over time: not only from night-to-night but also throughout the year and even from year-to-year. Compared to the objects in our own Solar System, the stars must be incredibly far away. Furthermore, in order to be seen from such a great distance, they must be incredibly bright.

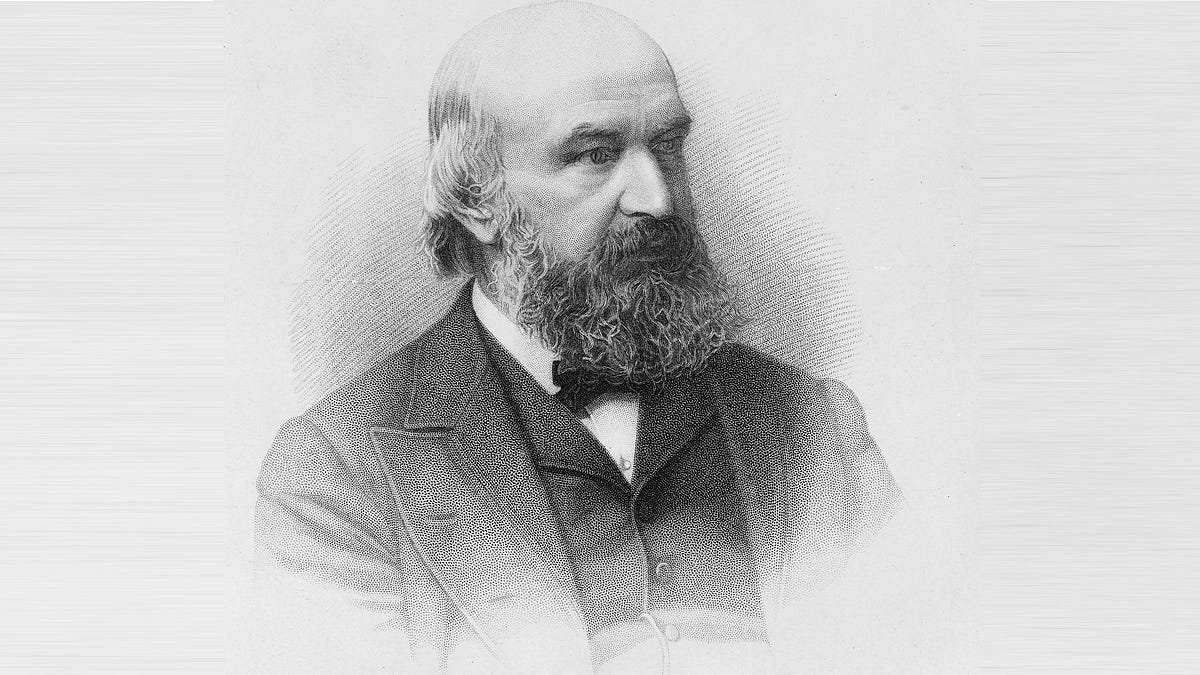

It only makes sense to assume, as many did dating back to antiquity, that those stars must be Sun-like objects located at great distances from us. But how far away are they? It wasn’t until the 1600s that we got our first answers: one each from Robert Hooke, Christiaan Huygens, and Isaac Newton. Unsurprisingly, those early answers didn’t agree with one another, but who came closest to getting it correct? The story is as educational as it is fascinating.

The first method: Robert Hooke

The simplest, most straightforward and direct way to measure the distances to the stars is one that dates back thousands of years: the notion of stellar parallax. The idea is the same one as the phenomenon behind the game we all play as children, where you:

- close one eye,

- hold your thumb up at arm’s length from you,

- then switch which eye is closed and which one is open,